KATE POOLE AND

THE HEALING POWER OF REGENERATIVE INVESTING

|

Kate Poole shares her talents as a comic artist to illustrate this story about the evolution of her personal investing philosophy, as she works to channel her inherited wealth to fund innovative projects and enterprises led by communities that have been the victim of an extractive economy.

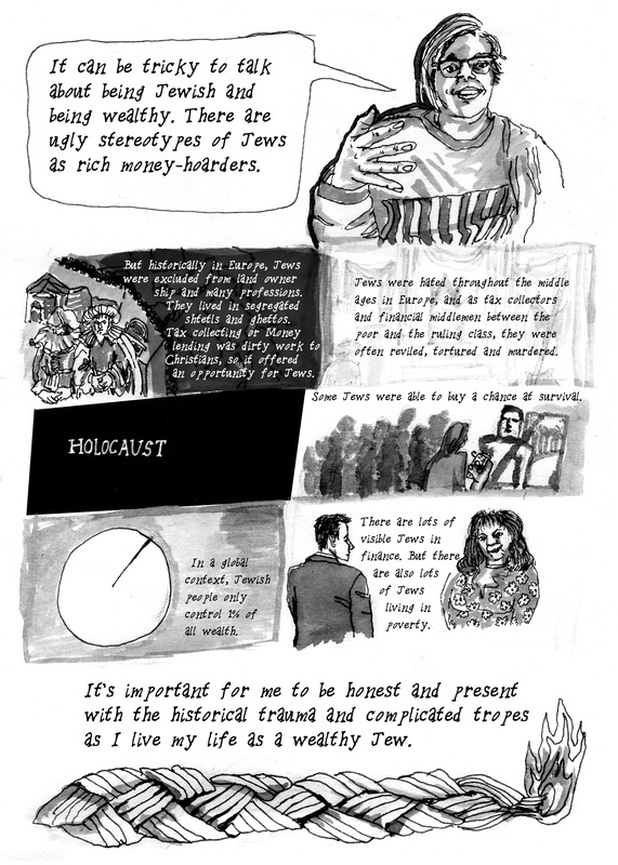

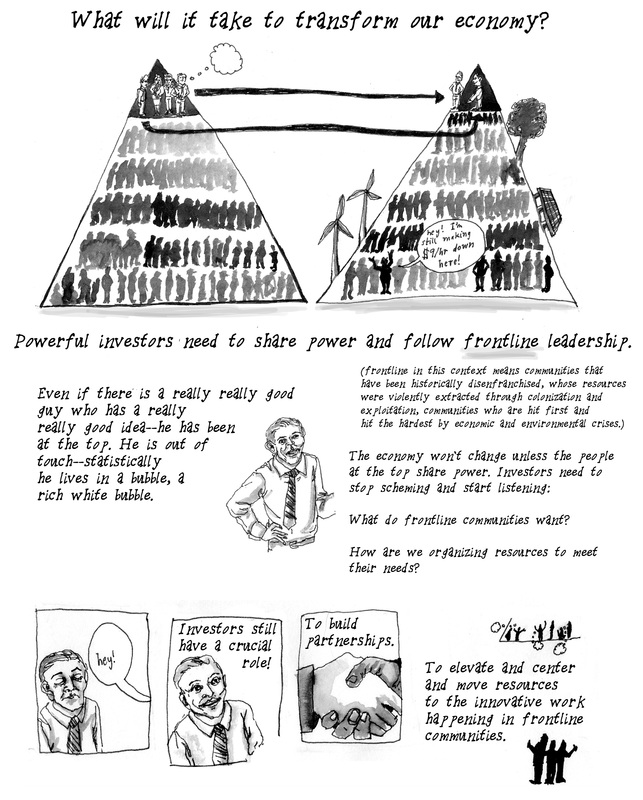

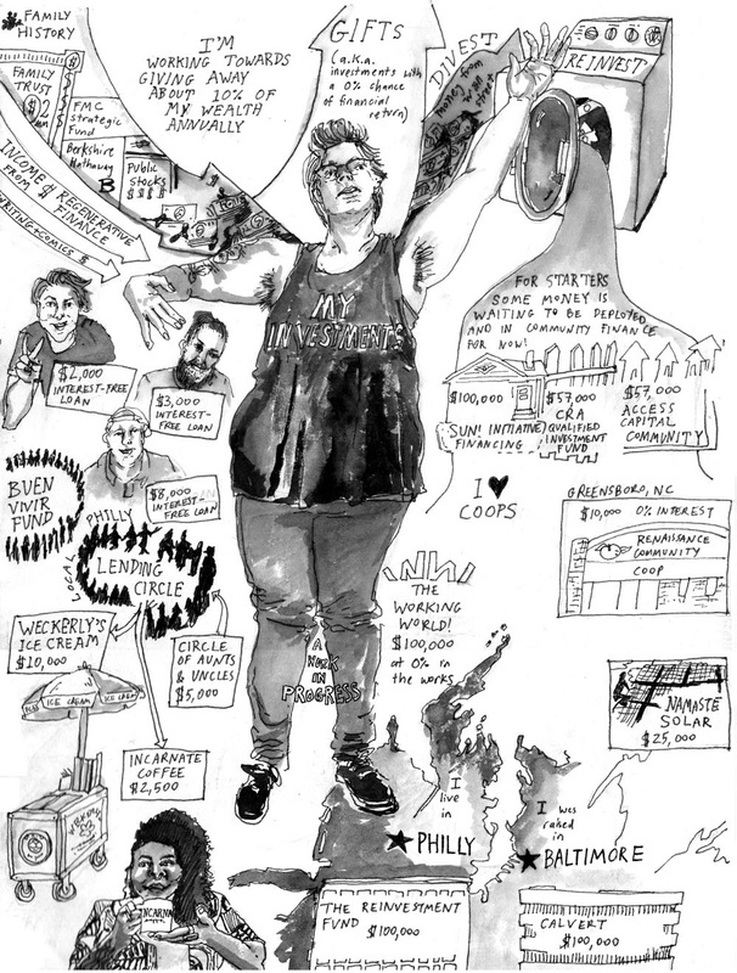

Kate Poole, 29, traces her inherited wealth back to her Jewish forebears on her maternal side. Her great-great-great grandfather, M.S. Levy, started up a straw-hat factory in downtown Baltimore in 1869 after moving to America from Germany via England. In the 1950s her family sold off a tract of farmland on the outskirts of Baltimore for the construction of the Beltway. The remainder of that land, located south of a major Beltway exit, now houses commercial tenants including a Target, a Hilton Hotel, and a bowling alley. Kate is among the partners in that family real estate investment trust. Over the years her family’s wealth also grew through traditional market mechanisms overseen by the wealth management business founded by her grand aunt’s husband. In America the experience of Jews was different, Kate acknowledges—the discrimination they experienced of a different nature. Her grandmother has shared stories of the infamous quotas once assigned to Jewish college applicants. And she is aware that her family members’ private wealth, and that of other Jewish entrepreneurs, came about because many established businesses in America simply did not hire Jews. Still, she says, her family was privileged as white Americans in having access to land ownership, investment capital, and protection from violence at a time when people of color did not have those rights." All of this has become a part of her consciousness and the way in which she views her responsibilities as a young woman of inherited wealth, acquired, she maintains, through an economic system that extracted it from both the land and labor. Kate began thinking differently about wealth and investment in 2007 when as a Princeton University junior she lived first at a Buddhist Monastery in India and later in the Santi Asoke Commune in Thailand. The latter was reacting in radical ways against the materialism of the country’s dominant Buddhist culture. “The attitude of the monastery was the more money you gained the more karma you were losing,” she recalls. “They held festivals where people gave away goods free or below cost and operated markets that transparently showed what the good was purchased for and what they were selling it for.” She wrote her senior thesis on Santi Asoke. After graduation she began reading E.F. Schumacher and other new economy thinkers, and worked as a researcher for Michael Shuman, the author of Local Dollars, Local Sense. Slowly she grew into her own personal philosophy and style of investing. Initially, when she decided to become more public about her views on how she wanted to deploy her wealth, her mother was protective, concerned that she might be taken advantage of. That said, Kate reports, “many of my family members are scientists so they are very open minded and curious about learning more and exploring more. After five years of conversations they are coming to understand what it means to have their values reflected in what their money is doing in the world.” Kate admires Movement Generation's philosophy, which speaks of a Just Transition grounded in building a new economic system “towards healthy, resilient and life-affirming local economies.” She shares their belief that “the heart learns what the hands do.” “If all you do is fight you won’t be able to build the system from love and hope,” she maintains. Kate tends to view traditional philanthropy and impact investing with a healthy dose of skepticism. “You have people of wealth who use foundations to fund a small handful of their favorite charities,” she reports. “That will never transform our economy. I am grateful for the leadership of rich white men and women who have shifted their wealth. But we will not create an equitable or new system if the same people who had wealth in the old system are deciding what they think will be useful and productive for us all. We need to be sure we don’t replicate the same power structure and same wealth inequality and the same sexism and racism that exist in the current economy. It has to be about redistributing wealth and transferring power and building trusting relationships.” Kate blogs on this topic here. For Kate, that means moving capital into the control of communities from which it has been extracted in the past. “That part of the work feels really regenerative to me,” she says. “We can trust communities and trust democratic governance.” Kate is focused on giving more boldly in ways that transfer that power—she’s most excited about investing in communities who have developed the infrastructure to collectively decide how to allocate investment dollars. This would include, she notes, “ building relationships and ways for individuals in communities to participate in a democratic process, canvassing and organizing to get community leaders in the room, deciding how to govern and structure a local fund, developing an advisory board representative of the different identities of folks in the community.” She has also worked to redistribute wealth through low- or zero-interest loans to friends, family, cooperative businesses, and groups that she is close to in the Philadelphia community she now calls home. As she works to transition and redistribute the wealth she’s inherited, the bulk of her investments are in CDFIs and in community investment opportunities focusing on racial justice and sharing power—that is where the goal of the investment is explicitly around racial justice and creating opportunities for shared decision-making.

Kate organizes to shift the shape of the economy as a member of Regenerative Finance, a collective of young people of wealth working to shift control of capital to communities most affected by racial, economic, and climate injustices. As a part of Regen’s pilot project she has extended a $10,000, zero-percent, ten-year loan, through The Working World, to the Renaissance Community Cooperative in Greensboro, NC. That loan is a part of the emerging Southern Reparations Loan Fund. A second Regenerative Finance project is the Buen Vivir Fund, an international loan fund centering power in the grassroots and in indigenous leadership, and co-developing terms of investment by convening investors and borrowers together. A third investment is in the Financial Cooperative with Working World, a peer network creating infrastructure for community-controlled loan funds focused on people of color and low-income leaders. Over the long term Kate sees herself building more experience around local lending so she can help and encourage others to embark on similar small-scale investing. “It is very scary at first, but there is really a finite amount of things you have to learn to do small loans,” she says. “Just to know what a promissory note is and how to set up a repayment schedule, so maybe you can lend a friend or someone you trust 500 dollars. The connective tissue that allows people to invest locally has been growing at such a rapid rate in Philadelphia and nationally. These connections can shift our local economies, and move money to poor folks and people of color that have been traditionally excluded from accessing capital. It is a really exciting time.” Kate is also deeply concerned that regenerative investing be an option not just for accredited investors but also for middle- and low-income people. She admires the work of the Boston Ujima Project, which is structured to allow both people of wealth and low-income co-invest in community projects, each according to their means, but with each investor having equal weight in decision-making around the investment project. ”That kind of democratic process builds and redistributes power, so communities can prioritize their authentic needs in how they're investing," she notes. But a larger question remains, she says. “How do we get people of wealth to identify how much is enough, and then for the money that they don’t need, for them to be able to confidently redistribute it with the level of generosity that low- and middle-class folks give and invest. There are studies indicating that low- and middle-class individuals give away a much larger percent of their income than people of wealth, and that their combined giving exceeds the giving of high-net-worth individuals and foundations. How do we frame risk and return so power can be shared equitably when people get together to make investments in the community?” Kate looks forward to the day when money returns to communities at a scale that can really effect change at a systemic level. Perhaps, she says, it will be the day in the not too distant future when 401k and pension funds give their clients the option to invest their funds at their own local, relational level. Kate Talks About The Regenerative Power of “Reparations” Investing

When I talk about reparations I am thinking about a moral imperative that gets folks to make radically different decisions about how their money is invested.

I don't think I can take responsibility for all of the moral failings of white people or rich people up until now. But it is important to learn about the history of wealth accumulation and the role of race and gender, and be thoughtful in how we are moving our money in response to that. It is not like I need people to sign a pledge that they agree with me around reparations. More that these community-led economic developments get resourced, that is the most important thing. I personally have experienced a lot of healing doing reparations work. There is a brokenness and there is a heaviness I carry because I have wealth from systems that I know have hurt people. I am personally nourished and more spiritually grounded when I fully embody my values by reinvesting wealth in the reparations framework. I get a tremendous amount out of working with the accumulated, historical baggage of my wealth and doing healing investments with it, redressing the power of extraction that came with what I inherited.” |

Please share your comments on

|