Redefining Resilience with Living Breakwaters

|

Tottenville exists in quiet remove from the City of New York, at the mouth of the New York Harbor and surrounded by the waters of Raritan Bay and the Arthur Kill. As local historian Barnett Shepherd describes it in his book The Town The Oyster Built, “far from the urban culture of Manhattan, Tottenville boasts a feeling of independence and isolation.” Originally inhabited by the Lenape Native American tribe, the village was later settled in the 1600s first by the Dutch and then the English. By the mid 1840s it boasted a diverse economy that included a thriving oyster and shipbuilding industry, and an abundance of farmland. By the turn of the 20th century, however, a combination of overharvesting, dredging, pollution, and disease had decimated the village’s oyster industry, and the shipyards that had been dependent on the oyster trade—there were once eight in operation in this tiny village—also fell into decline. Tottenville’s last working farm closed over 35 years ago, as land sold to house residents of the city seeking a more relaxed, country lifestyle. Although its maritime economy has shrunk to pleasure boating, sport fishing, a tug boat business, and a boat propeller manufacturer, Tottenville continues to this day to be, as Shepherd describes it, “a small coastal town…with characteristics unlike any other place on Staten Island.” The New York Bight’s funneling action intensifies wave action making Tottenville’s shoreline particularly vulnerable to erosion and storm damage. And when the oyster reefs disappeared from it, so did a critical protective storm barrier. |

Tottenville’s last working farm closed over 35 years ago, as land sold to house residents of the city seeking a more relaxed, country lifestyle. Although its maritime economy has shrunk to pleasure boating, sport fishing, a tug boat business, and a boat propeller manufacturer, Tottenville continues to this day to be, as Shepherd describes it, “a small coastal town…with characteristics unlike any other place on Staten Island.” |

|

The village’s peace and tranquility was then tragically shattered when Hurricane Sandy, a storm of historic magnitude, barreled into the New York metropolitan region in October 2012. In Tottenville’s peak storm tides reached 16 feet—almost five feet higher than those at the Battery in Manhattan. Huge waves breached the bluffs along the village’s shoreline where homes had been built in the 1980s on what had previously been critical wetland stormwater buffers. A 13-year-old Tottenville girl and her father were carried away and drowned when a huge wave ripped into their home. They were among 24 who lost their lives on Staten Island during the storm. In Sandy’s immediate aftermath, recovery efforts throughout the metropolitan area were understandably focused narrowly on rebuilding and on fortifying the shoreline against the next storm’s onslaught. But over time a quiet shift in thinking and in priorities began to happen, not only among the government agencies, planners, and designers tasked with rebuilding, but among the residents of the shoreline communities. The word “resilience” itself came to be defined in a broader and more nuanced context for those were experiencing firsthand what it really takes to restore damaged communities and natural systems. |

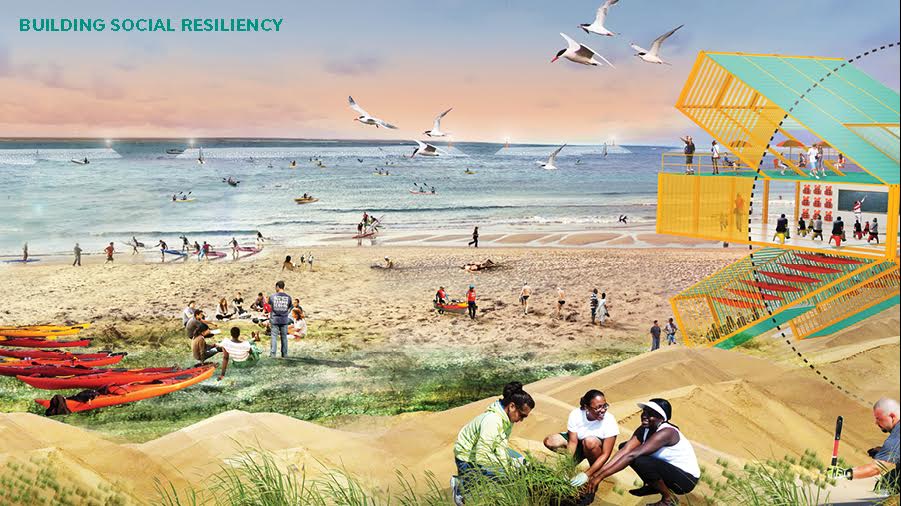

“We have been trying to redefine how the word resilience is used,” explains Lauren Elachi, deputy project manager of the Living Breakwaters project at SCAPE. “A lot of times it is defined as just the physical resilience of a wall along the shoreline. But what we are coming to realize is that the physical design is not the be all and end all. Ecological resilience is also key and so is social resiliency. So we have been trying to figure out, how can we combine those three things into our recovery initiatives?”

|

Tottenville’s Living Breakwaters was designed as an answer to that question. One of six winners of Rebuild by Design Competition, organized by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development in Hurricane Sandy’s aftermath, it will create a system of man-made breakwaters constructed of rock and bio-enhanced concrete units, seeded and hopefully fortified with the very same oysters that had once put Tottenville on the city’s culinary map. The plan is that as the oysters propagate, they will both strengthen the breakwaters over time and create the requisite conditions for more biodiverse marine life to flourish. The schematic design phase of Living Breakwaters is expected to be 30 percent complete by October 2016. If all goes as planned, the design will be finalized by the spring of 2018 at which point construction will begin. The scheduled completion date is late 2019. |

x

What began as a new kind of design competition in the devastating aftermath of Hurricane Sandy, has transformed into an innovative process that places local communities and civic leaders at the heart of a robust, interdisciplinary, creative process to generate implementable solutions for a more resilient region. Its inclusive process has since provoked a paradigm shift in the way that planners and governments approach both disaster response and emergency preparedness. Placing substantive collaboration between designers, researchers, community members, and government officials at the heart of an iterative creative process, the Hurricane Sandy Competition resulted in ten visionary design proposals that address the intersection of physical, social, and ecological resiliency. Seven of those designs are in the process of being implemented in the Northeast United States. Based on its success, Rebuild by Design has been used as a model for other processes. In the United States, President Obama launched the National Disaster Resilience Competition in June 2014, “inspired by the success of Rebuild by Design.” In the international sphere, the Global Resilience Partnerships launched a multi-phase resilience design competition in 2014 modeled after Rebuild by Design. In addition to as helping other regions rethink resilience before disaster strikes, Rebuild by Design keeps communities connected to the implementation of the funded designs; explores changes needed in policy, regulation, and operations; and researches the best practices in developing resilience. |

|

Engineers are now collecting site data, including information about the underwater topography of the Tottenville shoreline, what types of sediment and animals now exist there, and what the potential is for additional habitats and marine life when breakwaters are constructed. Their work is being closely watched as a pilot project to better understand the forces at play when storms hit elsewhere along the eastern and southern shores of Staten Island and the New York Harbor area in general, with the goal of adapting the project to these other vulnerable areas. “This is an unprecedented project for this region,” Lauren reports, “we want it to be a resource for the scientific community and the regional community to understand how these types of structures perform in New York, and how they could potentially be adapted and replicated elsewhere.” The New York State Governor’s Office of Storm Recovery has received $60 million in funding for the design and implementation of the project. For an infrastructure project of this magnitude, the level of intentionally planned community engagement is also unprecedented. Rather than relegate decision making to the “experts,” the community has been included in the shaping of the project from inception. Creating opportunities for residents to assume stewardship of their reclaimed marine heritage has been baked into the project, not just during the conceptual phase, but on an ongoing basis. The community has been invited into active engagement at facilitated meetings to think about how the breakwaters should be built. “We are starting to decide how long each breakwater should be and how far apart they should be from one another, and how far from the shoreline,” Lauren reports. “We have a touch screen PDF where you can see, depending on where you stand on the shoreline, what the breakwaters will look like from the beach. So people can start to visualize and say, ‘If I want maximum storm protection, well, I will have a 20-foot breakwater in front of my house.’ It is all a conversation about tradeoffs and what people want to prioritize. It is teasing out what are the priorities for the community and showing, for example, ‘if you create a 20-foot breakwater here then you won’t have your view. If you put it a bit further out you will have occasional flooding but a more of a view, what is more important?” While it might have been anticipated that residents would clamor for the tallest breakwaters and for maximum protection that hasn’t been the case. Most people who lived along the Tottenville shoreline agreed to take an adaptive approach, one that would make them safer against the next storm—maybe their basements would be flooded—but they would be able to enjoy their view and the natural spaces along the shoreline on the other 364 days when there was no superstorm. |

|

Based on community input, a community Water Hub facility is also proposed to be located on the shores of city-owned Conference House Park, providing access to the waterfront, and opportunities for birdwatching, kayaking, and general marine stewardship and shoreline education. The facility will likely include classrooms and labs, where students and teachers from the Harbor School on Governor’s Island and local Staten Island schools will be engaged in oyster restoration and reef building. John Kilcullen, Director of Conference House, is eager to see the Water Hub come to fruition, although the challenge will be to find additional financing for the ongoing activities that will hopefully take place there, since HUD funding will not cover them. Kilcullen sees the Hub as a way to lure visitors to his park, so rich in history and historic buildings, walking trails, an Indian burial ground, and potential for water-related activities. “Sandy is making everyone rethink the waterfront,” he says. “One of the wonderful things that happened through the Rebuild by Design competition,” Lauren explains, “is there was a lot of emphasis put on the building of stakeholder relationships —between government agencies and communities. |

|

We have been talking to the community for almost three years about this project and we think it really helped to build ownership within it,” she reports. “They are very knowledgeable about their environment, they are aware of erosion and of biodiversity.” The Living Breakwaters project was conceived from the outset as a layered approach to coastal resiliency, with a protective dune system combined with the breakwater structure. Another government-sponsored program, NY Rising, is working alongside Living Breakwaters on this project. Lauren notes that the complexity of the project is creating opportunities among agencies at the Federal, State and City level to engage in deep discussions about how regulations and policies need to reflect the systemic changes going on in the region’s climate. “Everyone is at the table,” she notes. “It is starting to spark an interesting dialogue about New York moving forward in the age of climate change. I don’t think this project will vastly change the regulations in New York, but it is sparking conversations about how do we become more adaptable and flexible along our shoreline because these storm events won’t stop happening. We need to think about what are the priorities for our regulatory community.” Lauren reports that sociologist Eric Klinenberg, an advisor to the Rebuild by Design competition who has studied how communities come back from natural disasters, has discovered that those that bounce back the best are not necessarily those with the most massive barriers against storm damage but those that have the strongest community ties. “Hurricane Sandy has catalyzed a lot of rethinking about rebuilding communities, on Staten Island but also in New York in general. How do we think about the next 50 years, not just the next year?” Lauren concludes. “It has been interesting to pull people out of putting one foot in front of the other and to think imaginatively about how we strengthen our communities as part of these kinds of projects.” An Update From Lauren Elachi, Living Breakwaters |