CONVERSATIONS

with Three Former Aldo Leopold Foundation Interns

|

JOSHUA LaPOINTE,

SOUTHERN WISCONSIN |

|

Here we share highlights of the conversation we had with three members of the 2001 Aldo Leopold Foundation internship program—Amy Sommers, Joshua LaPointe, and Steffan Freeman—as they describe how they have translated Leopold's Land Ethic in Central New York, metro Chicago, and Jackson Hole, respectively, into their workaday lives. Not surprisingly they have all stayed in touch with one another over the years, despite geographic distances, thanks to the bonds forged during a memorable time spent together with the spirit of Aldo Leopold in Baraboo, Wisconsin.

STEFFAN FREEMANLand Steward, Jackson Hole Land Trust

|

|

“BREAD AND BEAUTY GROW BEST TOGETHER. THEIR HARMONIOUS INTEGRATION CAN MAKE FARMING NOT ONLY A BUSINESS BUT AN ART. LAND IS NOT ONLY A FOOD FACTORY BUT AN INSTRUMENT FOR SELF-EXPRESSION ON WHICH EACH CAN PLAY MUSIC OF HIS OWN CHOOSING." — Aldo Leopold |

Lunch With Nina Leopold

When I came back from the Peace Corps in Niger where I had been a soil conservation volunteer, I wanted to work in restoration ecology. The first day of my internship at the Aldo Leopold Foundation we burned a prairie. We then got to participate in all the steps of restoring a prairie, from controlling invasive species, to collecting seeds, to planting prairie. We worked with landowners and learned about people’s different desires to do restoration— from the person who spent vacation time at a second home, to the farmer who wanted to respect his land. One of the most meaningful parts about my experience as an Aldo Leopold intern was getting to spend time at the Shack, even being out there on the coldest of the winter nights. Nina Leopold, Aldo's daughter, asked me in the morning if my toothpaste had frozen. At lunchtime we would go into the study center with its giant window overlooking bird feeders and prairie and sit with Nina.

She had a journal and she encouraged us to record first blossoms and first

bird sightings in it. Interacting with her was one of our favorite parts of the day. Leopold Country ... a Communal State of Mind I spent two years working at Troy Gardens, a 31-acre site that was acquired from the state of Wisconsin by the Madison Area Community Land Trust in 2001 and converted into a community farm, restored natural areas, community gardens, and mixed income housing. I remember one night being out in the prairie, we had harvested some hazelnuts, and we just sat around in a grotto cracking and peeling them. It was an amazing experience to have with people when you were in a city. None of us would have peeled the hazelnuts alone, but being out in that prairie, spending time as a community, made all the difference.

I enjoyed being in that urban setting just as much as I did the time I spent living on an island with only one other person and thousands of birds.

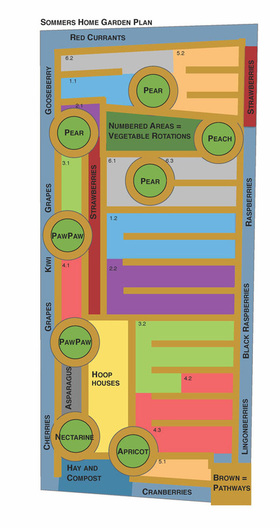

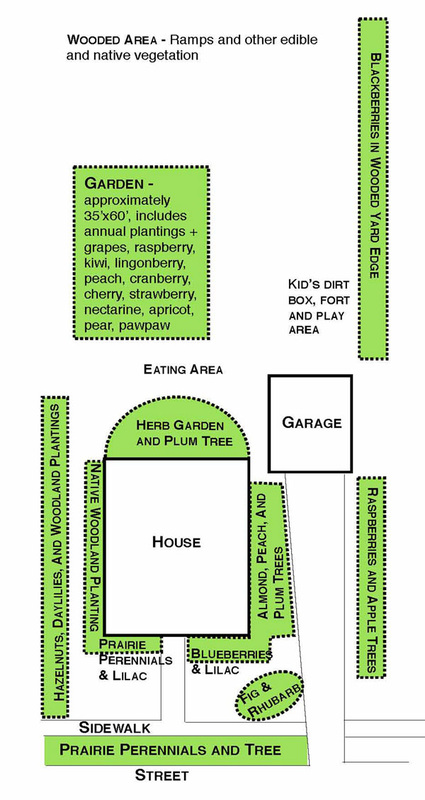

The Economics and Aesthetics of Private Land Restoration with the Community in Mind As a farm manager, I need to understand the land I work so I can preserve it for the long term, which for me also means continuity of economic income. Everything I do in farming also involves thinking of land as community. I designed my farm landscape to immerse people in edible landscapes that mimic and are intertwined with natural areas where you are getting both economic and aesthetic benefits. Unfortunately, we eventually learned that we couldn’t buy the rural farm site we were renting and had so carefully designed. But, we were able to turn that disappointment into a wonderful opportunity to transform our typical yard, inside a village, into a similar landscape. We are farming the half-acre lot for ourselves while continuing to intertwine edible and natural landscapes. The space between our sidewalk and the street isn’t your typical green lawn with a tree or two, but rather a prairie in its early stages, and I dream of the day when our fruit trees mature and our driveway is bordered with a profusion of peaches, apples, plums, and raspberries. |

|

It is interesting to talk to neighbors, to see what peoples’ interactions are with it. Mostly it has been positive. People ask about the different things we are growing and some are thinking about bringing some of those things to their own property. Sidewalks make a huge difference, people walk around the block.

You can’t expect everyone to pick up Aldo Leopold so how do you get it in someone’s view who is not necessarily thinking about land sheds and environmental impact?

How do you sneak in there and get them to talk about it and introduce them to Leopold and the land ethic? Being in a village situation is a huge advantage and you can reach more people.

Hardwired to Love Nature in all its Diversity At the Gaylord Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies where I did my Master’s work, they expect students to pursue a course of study that includes a social focus. For my Master’s thesis, I restored an area of prairie using a variety of seeding densities to study whether seeding densities affect the diversity of prairie. Diversity would indicate that the restoration was successful from a scientific standpoint, but I also wanted to look at whether or not diversity was important from a social standpoint. I then invited people, who either worked as restoration ecologists, were landowners restoring their own property, or had no real involvement in restoration work, to walk around the site and determine which plantings they thought were more successful and describe what factors influenced their decision. I hoped diversity would influence their choices. A farmer summed it up by saying, “I walked around and said, “where would my wife and I like to go for a walk on a Sunday afternoon?” and it was where there was a lot of different things to see.

Joshua LaPointeDirector of Construction, Applied Ecological Services

|

|

“WHAT IN THE EVOLUTIONARY HISTORY OF THIS FLOWERING EARTH IS MOST CLOSELY ASSOCIATED WITH STABILITY? THE ANSWER TO MY MIND IS DIVERSITY OF FLORA AND FAUNA.”—Aldo Leopold |

I graduated with a degree in biology and environmental studies from the University of Oshkosh, and we read Leopold’s Land Ethic as part of our environmental studies classes. When I heard about an opportunity for an internship with the Aldo Leopold Foundation, I jumped at the chance, and was given the opportunity in 2001 and was there for 18 months. I started in April, the beginning of burn season, and conducted my first prescribed burn on the Leopold Memorial Reserve. I continued working with private landowners as a part of the Blufflands Project to bring fire to some quality remnant communities in the southwestern part of the state along the Wisconsin River.

This internship opened my eyes to the field of Ecosystem Restoration, and because of my work with the Leopold family and the Foundation, I decided to dedicate my career to the restoration and protection of “the land,” as written by Aldo Leopold in the Land Ethic. I have remained in the field of ecosystem restoration for the last 12 years due to this internship. Forging Human Connections with Nature in Urban Areas I now work with a lot of different agencies, from federal to municipal, as well as developers and homeowners, to restore or enhance native diversity through the use of native species, bio- engineering techniques and through the removal of invasive species. We focus on restoring habitat in urban areas, from local parks and stormwater detention basins to large-scale restoration of forest preserves or rivers on the list of Areas of Concern. Local laws in the Chicago region now require developers to use native species for stormwater ponds and in open areas of developments. And the Federal Clean Water Act requires the private sector to do wetland mitigation when they damage wetlands due to unavoidable development. As a result, many developers who might have planted turf grass in the past are finding that that is not the best use of land, so some are starting to use prairie buffers instead, and they are planting a diverse prairie system that provides some wildlife benefits and walking trails. In those areas, you can use native plants for a lot of reasons, habitat and infiltration of water and carbon sequestration. It is a different aesthetic, but it is something that people are starting to adjust to rather than have clean, golf-course-like lawns or areas no one uses. It is amazing sometimes you are in these developments with hundreds of homes and you have these little connected paths of prairies and the kids are running around watching dragonflies and seeing native flowers.

It is really neat for a young kid to be able to go catch a frog in his backyard.

Melding Olmsted with Leopold in a Chicago Park Restoration Chicago’s Cook County has 66,000 acres of forest preserve lands, and the County works hard to restore the land and plant native species. So, we have an interface of humans and nature in a very urban area. The famous landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted designed the project we are working on now, Jackson Park, the site where they held the 1893 World’s Fair. They are trying to restore the park using Olmsted’s design philosophy while exclusively using plants native to the Chicago region.

Diverse native prairie restorations in the metro Chicago area provide blooming wildflowers from spring to fall. The wildflowers in turn support important but rapidly declining pollinators, such as native honeybees, that require nectar sources throughout the year.

We are taking all the areas around two lagoons and planting hundreds and thousands of native plants to create a native ecosystem in a park setting where you have hundreds of thousands of visitors a year. So it is melding something of Leopold and Olmstead into one project.

Honoring Biodiversity in all its Diversity There are some major challenges we will have to face in our world, including ongoing threats to biodiversity. We need to be able to interact with all species and not just choose the few we like – it’s important to understand ecological connections and how we can support and enhance the world around us by planting native species on our prairies and forests. This goes along with efforts to protect and enhance clean water, clean air, to build and protect our soil, and to try to create habitat for our local pollinators and other insects and on up the food chain. There are so many things to be hopeful about. I think people around the country are beginning to understand the interconnectedness of all things and how we all need to get along and work together to thrive.

|